The historic strike that rattled Crimea

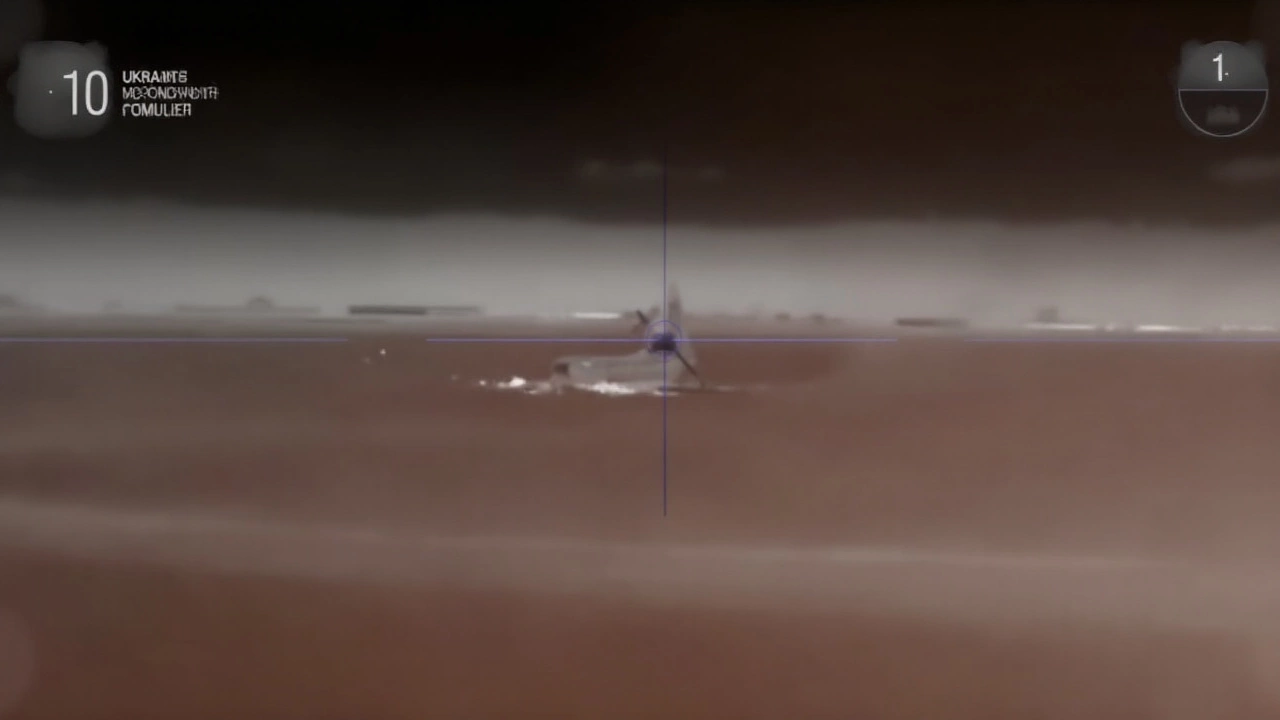

On September 21, 2025, a squad of Ukraine’s Main Intelligence Directorate, known locally as the "Prymary" or "Ghosts," pulled off a strike that none of us thought possible. Using cheap, off‑the‑shelf kamikaze drones, they hit an airfield in Russian‑occupied Crimea and blew up two Be‑12 "Chaika" amphibious aircraft and a Mi‑8 helicopter. The footage released by Kyiv shows the drones’ eye‑view right before impact, with one of the planes clearly marked with Bort number 08.

The airfield is believed to be the Kacha base near Sevastopol, a spot that has seen multiple Ukrainian raids over the past months. What makes this particular attack stand out is the target itself – the Be‑12, a twin‑turboprop seaplane that first flew in 1960 and has been a rarity in any modern air force. Until this day, no combat loss of a Be‑12 had ever been confirmed.

Ukraine’s special forces didn’t just stop at the seaplanes; the same drone assault took down a Russian Mi‑8 transport helicopter that was parked nearby. The operation fits a pattern we’ve been watching: Ukrainian intelligence units repeatedly striking high‑value assets in occupied Crimea, from radar stations worth $100 million to multiple Mi‑8s, using fast, low‑cost drones that can be launched from inside Ukraine’s own borders.

Implications for Russian naval aviation

Why does the loss of two Be‑12s matter? For one, Russia’s fleet of these aircraft is incredibly small – estimates put the total at under ten operational machines across the entire country. Losing two at once could shave the fleet in half, dramatically reducing Russia’s ability to patrol the Black Sea for submarines and to hunt Ukrainian drone boats that have been buzzing the waterway.

The Be‑12 isn’t just a plane; it’s a platform packed with expensive sonar, radar, and weapons systems designed for anti‑submarine warfare (ASW). Its twin turboprops let it cruise at about 330 mph and climb to 10,000 feet, giving it enough range to cover large sea areas without needing a runway. In the current war, Russia has used these seaplanes to chase down Ukrainian unmanned surface vessels that try to disrupt shipping lanes and even to drop depth charges on suspected submersibles.

With half the fleet potentially out of action, Russia will have to lean on older, less capable assets or scramble other aircraft to fill the gap. That could push the Russian navy to rely more on land‑based maritime patrol planes, which lack the flexibility of a true amphibious platform that can land on water and take off again in a pinch.

Below are a few key specs that illustrate why the Be‑12 has been such a valued tool for Moscow’s naval pilots:

- First flight: 1960 – a design that’s survived three generations of warfare.

- Powerplant: Two turboprop engines delivering roughly 4,000 hp total.

- Maximum speed: 530 km/h (≈330 mph).

- Operational ceiling: 3,000 m (≈10,000 feet).

- Primary role: Anti‑submarine warfare and maritime patrol.

In short, the Be‑12 is a niche but powerful piece of hardware, and taking two of them out in a single night sends a clear message about Ukraine’s growing proficiency with drone warfare. The success also highlights how Ukrainian intelligence has evolved from a passive information‑gathering body into a proactive strike force that can hit targets deep in enemy‑held territory without putting pilots in danger.

Analysts are already speculating on the next steps. Some think Kyiv might target the remaining Be‑12s with similar drone swarms, while others expect Russia to double down on air‑defense measures around Crimea’s airfields. One thing is certain: the battlefield in the Black Sea region is changing fast, and cheap, disposable drones are now a core part of that shift.

More Articles

Best Rural Pub: The Plough in Wigglesworth leads Julian Smith’s Local Pub Awards 2025

The Plough in Wigglesworth has been named Best Rural Pub in Julian Smith MP’s Local Pub Awards 2025 after public nominations and voting. The Black Swan in Ripon took Best Pub overall, with other winners including the Woolly Sheep Inn in Skipton and Sera from The Albion, Skipton. The awards spotlight local pubs as community hubs and employers across Skipton and Ripon.

Rashid Khan’s 200th ODI Wicket Powers Afghanistan Past Bangladesh in Abu Dhabi

Rashid Khan claimed his 200th ODI wicket as Afghanistan edged Bangladesh in a rain‑shortened match at Abu Dhabi, leveling the series after a 3‑0 T20I loss for the Afghans.

Trump’s Tariff Plan and $2,000 Dividend Proposal Risk $22K Household Losses, Warn Economists

Trump's April 2025 tariff plan and $2,000 dividend proposal risk $22,000 lifetime losses for middle-income households, with economists warning of GDP declines, capital flight, and unsustainable debt — even as a temporary China deal offers only fleeting relief.